Center for Chinese Music and Culture (CCMC)

Archive Explorations

Lou Harrison’s Qin

First published on March 10th, 2023

On a bed of lilac silk, proudly displayed in the Center for Chinese Music and Culture’s archive collection, lays an instrument named the qin. A glossy finish coated its long wooden body, the shine dulled from years of use by the famous musician that once owned it. This qin belonged to Lou Harrison (1917-2003), his hands once skillfully gliding over the seven taught strings as he studied ancient melodies. This qin was donated to the Center from Fredric Lieberman’s family (a story for another day.)

Upon further research, I discovered that Harrison was one of the greatest American composers of the 20th century. He borrowed unique sound elements from Asian music and created innovative compositions, resulting in a whole new wave of contemporary Asian-American music. His endeavors led him to a friendship with zheng virtuoso, Liang Tsai-Ping, and in 1962, in the balmy heat of Taiwan, Liang taught Harrison the art of Chinese Music.

Looking at the delicate curve of the instrument and the heartfelt writing carved in the back, I learned that this qin was a gift from Liang to Harrison to commemorate their friendship. Every qin has a name, and Liang titled this one “Sharing Heartfelt Wishes.”

While both men were most skilled at the zheng, Liang chose the qin because of its ancient connection with friendship. One of the most famous songs for the qin is “High Mountains Flowing Water,” and this piece exemplifies their friendship. High Mountains Flowing Water is also an ancient and deeply symbolic phrase that extends past companionship and into profound understanding of one another. Harrison and Liang played music together, passing on the songs of their souls.

The writing on the qin reads as follows: “The famous contemporary American composer and guzheng expert Lou Harrison is passionate about ancient Chinese music. Upon his request, I chose this guqin for him and named it “Sharing Heartfelt Wishes,” depicting long-lasting friendship through the playing of music.” –Liang Tsai-Ping, December 1986.

—Nina Meer

Liang Tsai-Ping and the “Reunion at the River of Heaven”

First published on February 22nd, 2023

Tucked between faded cardboard vinyl sleeves and yellowed plastic protectors, I found a collection of vinyl by a musician named Liang Tsai-Ping (1910-2000). While the archival collection at the Center for Chinese Music and Culture has boxes upon boxes of albums, something about these caught my eye.

What drew me in might have been the orange cover, once bright and flashy but now a wistful tan, or the serene focus on the musician’s face, but the music spoke for itself. Listen to the quick plucking of the strings followed by the whine of the notes, almost as if the song was guiding you through the circles in a sand garden.

I discovered that Liang Tsai-Ping pulled the zheng from the annals of history and was the first artist to record and release Chinese music in North America. The zheng, a Chinese pluck-string instrument with a long soundbox, is coincidentally what the Center’s director, Dr. Mei Han, plays!

Liang’s mastering of the zheng attracted friends from all over the world, including famous American composer Lou Harrison. (That’s a story for another day, though!) With his endless ambitions and the astronomical surge in popularity for vinyl, Liang’s music found a home on the shelves of open and inquisitive minds.

The highlighted song for today is called “Reunion at the River of Heaven,” the fourth track in Liang’s 1965 album “Chinese Masterpieces for the Cheng.”

—Nina Meer

Dr. Fredric Lieberman

March 1st 1940- May 4th 2013

This new feature highlights interesting finds from the audio collections of the Center. The majority of the CCMC’s collection is from the personal library of the late ethnomusicologist Dr. Fredric Lieberman. In this article, we honor his life and work.

Among ethnomusicologists—people who study the relationship between musical sounds and human cultures—Dr. Lieberman is known for his contribution to the study of Chinese music. In order to satiate a growing demand from European and American scholars for primary source material on Chinese music, Dr. Lieberman traveled extensively in Taiwan during the 1960s and 1970s making contacts with local musicians and conducting recordings of performances on “national instruments” like the qin (7-string zither), zheng (16-string zither) and erhu (2-string fiddle). Many of the recordings he collected are now in our archives.

Along with this fieldwork, Lieberman published several written works comparing the music of China to that of neighboring countries like Japan, Korea, and Laos. He examined the way that different styles of Asian music influenced one another and speculated on the origins of instruments, scales, and performance settings found across the continent. While visiting Taiwan, Lieberman also bought hundreds of 7”, 10”, and 12” records produced by China’s burgeoning recording industry and brought them back to the US.

Lieberman’s contribution to the study of Chinese music is among his major accomplishments, but fans of the endlessly touring San Francisco rock group The Grateful Dead may recognize his name from one of the three books he co-wrote with percussionist Mickey Hart. A proud denizen of San Francisco’s bay area, Lieberman supported The Grateful Dead throughout their multi-decade career and played a pivotal role in the creation of the band’s archive at the University of California at Santa Cruz. Lieberman and The Grateful Dead shared a prolonged fascination with American “vernacular” styles like jazz, blues, folk, country, bluegrass, and rock music.

Lieberman’s connection to The Grateful Dead may seem disconnected from his earlier contribution to the study of Chinese music, but it in fact demonstrates his unwavering dedication to highlighting the connections between different musical traditions rather than focusing on their differences. Both Chinese and American traditional styles involve the use of harmonies and scales that violate the rules of European tonal harmony. Lieberman’s main late-career work centered on Lou Harrison, a composer who intentionally violated these same rules by writing music based on “microtonal” scales that sound “out of tune” to listeners solely acquainted with European Classical and Romantic-period orchestral music.

Dr. Lieberman’s life and work will undoubtedly continue to influence young musicians in the United States and abroad whether they know his name or not. His dedication to expanding the realm of musical possibility by locating the tonal connections between seemingly disparate musical styles has already had a profound impact on popular music. There is much more to be learned by delving into his personal collection. I hope you will join us and enjoy the many fascinating stories about Chinese music that we uncover.

September 13, 2016

Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy and Beijing Opera

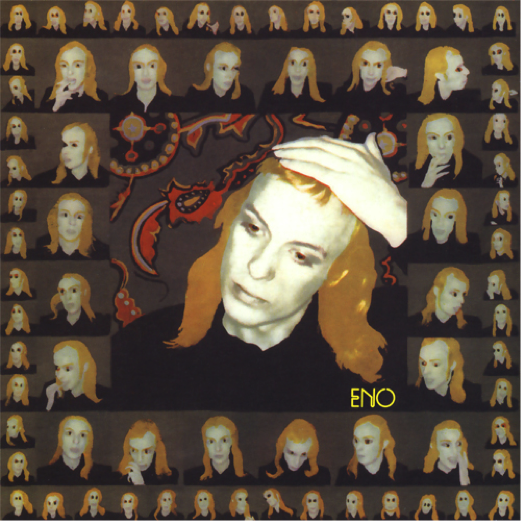

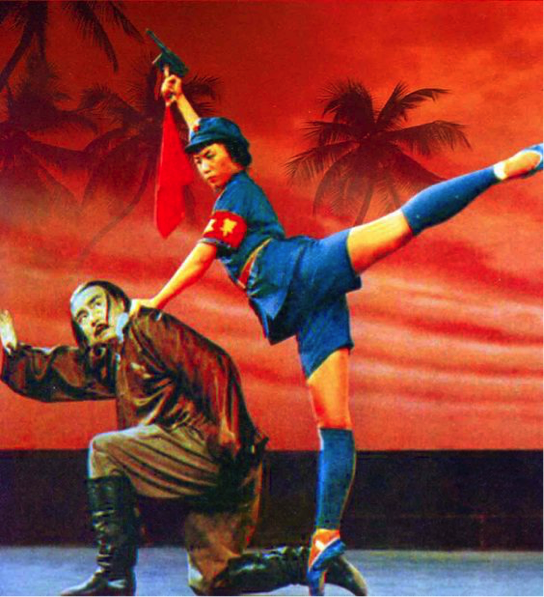

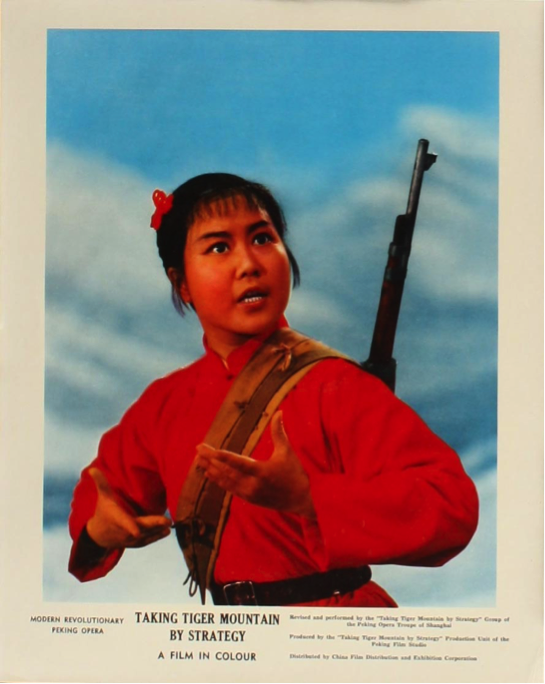

Judging from the critical reaction generated by the 1970 Beijing opera Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy and the 1974 experimental rock album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), it is safe to say that the two works share an auspicious title. Brian Eno, the producer and performer of the latter work, wasn’t entirely familiar with the sound and style of Beijing opera when he recorded his album. He was, nevertheless, so inspired by a collection of photos from an early performance of the piece that he created an entire set of songs based on them. Looking at the performance photographs featured on the sleeves of the hundreds of 10-inch and 12-inch Beijing opera records that Dr. Lieberman brought back from Taiwan during the late 1970s, it is easy to understand why Eno found the images from Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy so captivating.

People seeing performance photographs of Beijing operas for the first time will likely be drawn to the exaggerated and emphatic poses of the onstage performers as well as their emotionally intense facial expressions. Unlike many other forms of theater, Beijing opera eschews any attempt to directly imitate everyday life. In fact, actors in Beijing operas usually intentionally exaggerate everyday gestures, words, and facial expressions, seeking to thereby elevate their emotional impact on the audience. Writers of Beijing opera generally draw their storylines from historical and legendary accounts of China’s past. For example, Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy is based on a fictionalized historical account of a man named Qu Bo who posed as a bandit in order to help the Chinese government shut down a large crime syndicate thriving during the Chinese Civil War of 1946. This may remind some readers of German composer Richard Wagner’s propensity to include real and legendary German history in his work. However, those unfamiliar with Beijing opera should be cautious about drawing too many parallels between the style and European forms of musical theater.

Indeed, beyond the fact that they are both forms of musical theater, Beijing opera and European opera share very little in terms of musical or visual style. While French, Italian, and German opera singers are primarily concerned with making their voices carry through large performance spaces, performers of Beijing opera are instead foremost focused on wedding their often-acrobatic motions and pantomimes to sudden shifts in the volume and timbre of their musical accompaniment. Small ensembles of percussive and melodic instruments led by a Jinghu (2-stringed Chinese fiddle) generally provide this accompaniment. Beijing opera resembles modern western compositional music far more than it resembles earlier harmonic forms of operatic classical music. Listeners will find many unfamiliar harmonies and timbres likely to startle them upon first exposure. That being said, it is important to keep in mind that the startling nature of Beijing opera is quite intentional.

Beijing operas were composed and performed in China as early as the 18th century, but nearly all of the records that Dr. Liebermann purchased to represent the style in his collection were composed and recorded during a watershed period in the late 1960s and early 1970s when Chinese government officials chose the style to represent the revolutionary character of their era. Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy is one of eight operas composed at this time as “models” for future composers tasked with creating state music. These eight operas were intended to display the full emotional range of the Beijing form and also demonstrate how the politics of the Chinese government could be expressed in Chinese art. From its early conception, Beijing opera was more political than many other styles of Chinese music, but the operas composed during the Cultural Revolution are especially radical. The costumes in operas like Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy are stylized versions of the real military uniforms worn by Chinese soldiers of the period and often include firearms.

There is currently a renewed interest in Beijing opera worldwide as troupes of performers become increasingly common outside of China. While the politics of the operas created during the 1960s and 1970s are now very controversial—shades, once again, of Wagner—musicians and fans of music worldwide still appreciate the sonic and theatrical details of the works. While the style’s confrontational attributes serve to make it an acquired taste for some, many listeners will find the music itself to be exciting and refreshingly new. Some will also likely come to appreciate the aesthetics of the works as well.

Contact:

Dr. Mei Han

ccmc@mtsu.edu

615-904-8121

Physical location:

503A Bell Street, Suite 1600, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

Andrew Woodfin Miller, Sr. Education Center

Fall 2025 Hours:

weekday 10 am - 3 pm

Mailing address:

MTSU Box 168

1301 E Main Street

Murfreesboro, TN 37132-0001